Apprentice

Tyrone Belgarde: One Determined Construction Estimator

It’s hard to believe that at one point Tyrone Belgarde had an attitude problem. Nowadays, the Oregonian is a valued, longtime member of the team at Knife River’s Tangent, Oregon offices. The 39 year old has been with the company for nearly 20 years, and has risen from an entry-level Laborer position on the grading crew to his current position as Construction and Estimation Manager.

“He’s one of the nicest guys,” his coworker says to us admiringly when we visit to talk to Belgarde about becoming a building trades leader.

Maybe he always was the helpful man we see during our interview, but circumstances were such that in his early days as a worker, Belgarde was a bit difficult to keep employed. His parents divorced when he was five years old, leaving his dad to deal with his addiction problems apart from the family. Belgarde and his mom and siblings moved around a lot. He went to boot camp before his senior year of high school, and graduated from South Albany High School by the skin of his teeth before returning to boot camp for his second stint. He enrolled and dropped out of Linn-Benton Community College at age 18. “I didn’t have enough money, was too immature to go to college,” he says.

Shortly thereafter he found work at an underground utility company in Salem. “It was not good,” he said. “I was a jerk and got fired – I deserved to get fired!”

Belgarde says he’s not sure what caused his transformation into responsible worker, but it happened sometime during his years at Knife River (originally Morse Brothers when he was first hired).

“It was quite a culture shock,” he says of the professional pace of jobs there. But he found his rhythm, landing a spot as an apprentice in the paving crew. “They said ‘if you want us to invest in you, to teach you how to pave, this is your opportunity.”

So he dug in, moving from Paving Crew Laborer to Roller Operator, to Screed and Paving Operator, to Paving Foreman, working jobs from Portland to Eugene. By the time he was 29, he had two daughters and a son. He now teaches occasional classes for Grand Ronde and Siletz Native Americans through the Northwest College of Construction. He honors his father’s heritage by participating in tribal events, sending his kids to culture camp to learn about being Native.

But still: “When I talk about things like vision – I don’t have a long term vision. When people talk about your five year goal – well I have a goal to get through today.”

That attention to the task at hand, perhaps, is part of what makes him a good leader. “Identifying a problem, figuring out your options, and acting,” Belgarde says, is his general way of moving through work. He places a high value on teaching, as a leader in his workplace.

And when he sees a position he wanted, he goes for it whole-hog. Take estimation work – Belgarde showed up to observe Knife River estimators for free during part of a winter, absorbing the information with such commitment that management took him on, first at minimum wage, then as a full-fledged member of the team. Now he’s a manager who is working on a $10 million Newport airport project, the only worker in his part of the office without a college degree.

He says that working in the trades has made it possible to provide for his family, and it’s satisfying to boot. “I can’t drive anywhere without seeing a driveway or a parking lot that we’ve built. You remember all the funny stuff from that site, like the person who spilled oil all over the place,” he laughs.

When he’s asked about advice for beginning building trades folks, Belgarde is hardly at a loss. “Always move forward. Always ask questions about what you need to work on. Don’t expect others to do it for you.”

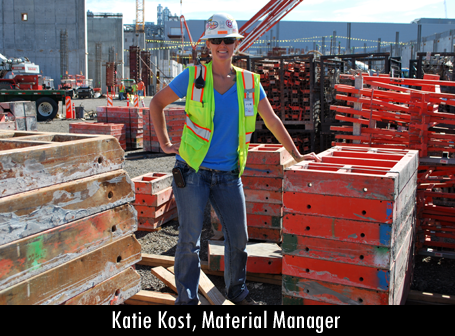

Katie Kost: Graduating to a New Level of Leadership

Anyone who thinks that major construction sites are no place for a woman to spend her professional life should talk to Hoffman Construction Material Manager and Laborer Foreman Katie Kost. She’s found a unique job in the building trades that fits the arsenal of skills she gained in college and in various jobs. Plus, it’s meshed well with her life outside of work. Kost was on the job up until two weeks prior to giving birth to her baby last year.

Not to say that life has been free of challenges. “You have to have tough skin,” says Kost. As a female, “you just have to work hard. It’s not an easy trade. But for me, who has been to college, and wanted to do sports marketing, it’s been great.”

After earning extra money by delivering Domino’s pizzas for $7/hour, Kost graduated from Barlow High School at 18 as a star volleyball player. She received a full ride from North Carolina State to play her sport. She wound up transferring to Portland State her senior year, and left that school with her degree in business management.

After college, Kost wound up working at Lowe’s, then doing inventory at a wholesale auto dealer. She became close friends with a surveyor who had ties to Hoffman Construction, and through the strength of her inventory managing experience, Kost got her first job in that area with the company in 2005.

But Duane Meduna, a Hoffman Superintendent, was impressed by what he saw, and invited Kost to step into the “hybrid job” (as Kost puts it) of Materials Manager/Laborer Foreman. For the position, Kost spends time in the Hoffman offices, but also out on building sites, advising workers on how to keep track of expensive supplies. She’s worked on the concrete crews as well, she says, to get a hands-on feel for the work.

Before Kost got on the job, she says, losses in materials per job could sometimes total $200,000. She’s been able to keep that figure down to $1,000, as was the case when Hoffman worked on Portland’s Cyan Building. “I would say that’s when I gained the most respect,” Kost says, looking back on that project. “She’s a very important part of the job,” affirms Meduna. “When no one is in her position, the guys slowly stop taking care of business”, he says.

One challenge in her position is getting people to recognize her authority as a young woman. “It took a year or two before they’d really listen or respect me,” she says – many of the people whose work she oversees are many decades her senior. “I’ve learned that you just need to put your foot down,” she reflects when we ask her the secret to gaining respect on the job.

But Kost’s capability is undeniable. She’s praised for her attention to detail, and the precision with which she does her work — her value to the company is well established. Plus, she’d have a hard time going back to a desk job. “I really like being in different places all day, not just sitting behind my computer.”

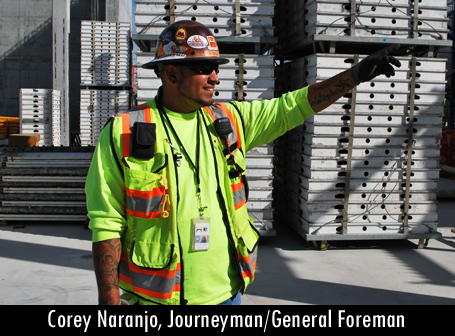

Cory Naranjo: A Good Fit for Foreman

“If I wasn’t in the trades?” General Foreman Cory Naranjo considers the question as the walkie-talkie affixed to his vest crackles to life. He’s stumped. “I never really considered it,” he concludes. “I’d probably be working an office job, hating life.” Laughter.

It’s true that Naranjo does seem incredibly suited to his leadership role at Hoffman Construction. He is currently working at the Intel building site Hoffman Construction has been developing in Beaverton and he has spent his entire career in construction at this very company, starting as a Carpenter Apprentice. “I guess that’s a big accomplishment,” he reflects somewhat modestly.

Naranjo had plenty of options when it came to jobs. He got good grades in high school, started working early, at 15 when he did a turn on a summer work crew for the city of Woodland, Washington, where he grew up with his dad, who worked for Weyerhaeuser (and who moved here from Jalisco, Mexico) and mom (who has Italian heritage) who is a registered nurse.

That first summer, he worked at flagging, cleanup, and weeding around the city. But in 2000, when he graduated high school, he was put to work right away in a leadership position as a lead man at General Steel loading trucks.

“It was a lot of responsibility,” he recalls. Maybe that’s why, when he started dating his now-wife Kathleen and her father-in-law impressed upon him the earning potential and the benefits that could be gained from a career in the trades, he reconsidered his plans for higher education. In 2001, he joined a carpentry apprenticeship program at Hoffman.

“I was green – it was interesting,” he says lightly. “You don’t know what you’re getting into until you’re out there doing it. You’re working in all kinds of weather and elements as opposed to sitting in an office all week long.” He learned lots of skills in residential and house building, a big contrast from the large-scale work he’s engaged in when we catch up with him at Intel.

“Hoffman is a good company,” Naranjo says. “We’re like family here. Everyone’s mellow, takes into consideration what’s going on.” He counts as his biggest accomplishment his quick rise to Foreman with the company – his first job as a lead he spent learning alongside Amos Austinson, now working as a Field Superintendent, who Cory credits with teaching him a lot of what he knows. Naranjo’s first turn as foreman he spent working with his friend and teacher on the Waterfront Pearl condos in downtown Portland.

How did Naranjo manage his relatively quick rise up the building trades ladder? He reckons it has to do with being a hard worker and that, “a good leader has to be knowledgeable, willing to listen to the group of workers that you got, willing to admit when you’ve made a mistake.” Now his goal is to be a Superintendent like Austinson.

When asked if he has ever experienced challenges on the job as a man with Latino heritage, Naranjo shrugs. Not personally, he says – though he has seen the obstacles that can come to those for whom English is not their first language. “People kind of get aggravated, and it can play a role in who gets hired.”

But now that Naranjo is a father – Christopher was born to the couple in 2002, with Lily and Olivia quick to follow – the benefits of being in the trades are clear. “I was able to purchase a house when I was 21,” he tells us. His wife is able to be a stay-at-home mom, which he’s proud of. “We have a pretty nice lifestyle – the benefits of hard work pays.”

Danielle Zoller-McKenzie: Iron in the Blood

Danielle Zoller-McKenzie has union Ironworking in her blood — she grew up with a dad, brother, cousins and uncles in the trade. But while her family didn’t discourage her from pursuing work in their field, she wasn’t exactly encouraged to try it, either. “They thought I was going to be too small,” she says.

But a summer job as a hodcarrier – or “hoddie”, as she was dubbed by the masons she worked with convinced her she was more than up to the task. “The camaraderie is what I really liked,” she told us. “My brother worked there too. To be a woman and a hard worker is a different kind of feeling than you get than just being a ‘woman worker.’ The praise you get from working really hard, it’s just a big deal.”

After graduating high school, she worked in the shipyards, confirming her love of working in the trades. She applied to the Ironworkers apprenticeship program, and after a year of waiting – somewhat impatiently, she adds — she was in the door.

“I knew when I got into this trade that it’s a man’s world,” Zoller-McKenzie says. She was treated differently by coworkers, held to a different standard. Everyone in the program could see the double standard, but she opted to focus all the more intently on her work in the face of adversity. “It’s always paid off for me to take the high road,” she says. “Although that may not be my first instinct.”

Zoller-McKenzie started her career back in 1998 working on bridges and rebar projects. After two years, she came to Carr Construction, and has worked for the same company ever since, drawing on an enduring network of supportive co-workers rather than surfing from job to job. She says she values security over novelty: “I’d rather wait out the slow times.”

In 2000 as an apprentice, she became eligible to start work on her welding certification and passed the initial training in only three weeks. She pressed on, getting incremental raises and working hard as a “grunt,” as she puts it. She passed her journeyman’s trade certification in 2002 and has since advanced to her current role as superintendent. Through the years she took a number of OSHA classes and is now starting to teach apprenticeship training classes herself.

“I got lucky as a female,” says Zoller-McKenzie. “Because I did make friends and they took me under their wing.” (Continuing in the tradition of paying it forward, she’d like aspiring Ironworkers to know there’s now a smart phone app to aide with the math-heavy art of angle finding. Yes, it’s called Angle Finder.)

Her work has afforded Zoller-McKenzie some memorable times. She’s had a one and a half day welding assignment turn into a gig that lasted over a year, and a job in Terrebonne, Oregon for which she got to do her work 150 feet off of the ground.

The job is not without its downsides – Zoller-McKenzie says the weight of working outside in all weather conditions is getting hard to bear as her body ages. And she says she’s had to sacrifice any semblance of a “normal” family life: “The crazy schedule of this job demands pretty much 15 hours a day.”

But she likes this work. Zoller-McKenzie’s career path has taken her from journey-level worker to crew supervisor — nowadays she also performs crew foreman duties as needed, delegating tasks and being responsible for safety compliance.

She’s proud of what she does. She makes good money and, as she tells us in our interview “the kind of fun you can have on a job is unbelievable.” Looking forward, she has plans to pursue her OSHA safety supervisor certification, and would love to work as an engineer for that agency one day.

This multi-generation Ironworker’s advice to new female tradeswomen? “There’s always going to be some guy who will blow you off because they don’t believe women should be in this job. Have a thick skin. Accept what is, and find the positives.”

Dan Rodriguez: A heavy equipment operator who lives lightly

Dan Rodriguez says he’s pretty happy having spent the past 23 years being, as he likes to call it, “a dirt hand.” After meeting the guy, you tend to believe him – he’s led quite a life mastering the art of operating heavy equipment.

The expert dozer and scraper operator has his father to thank for his well-suited career – his dad suggested Rodriguez sign up with Local 701 Operating Engineer Union for heavy equipment operator training decades ago, after Rodriguez had spent his first five post-high school years indoors at a machinist shop.

“I learned I actually liked the smell of diesel engines and working with dirt,” the Klamath Falls native tells us.

Young Rodriguez moved to Eugene for his first trainings with Operating Engineers Local 701 – the first journey in a career that would bring a lot of traveling for the small town boy. A short time later, he wound up moving again. This time, it was to Boardman, Oregon, where he completed his pre-apprenticeship training. At the time, Rodriguez was working as an oiler. (It was several years before he “got into the seat.”)

Those first few days in Boardman, Rodriguez realized that education would be an ongoing process in this line of work. “They put me on a job where I was responsible for maintaining and greasing the plant and the equipment,” he says. “I had to figure out so much that at first, it took me 19 hours to get it all done. But I stuck with it, and later I was able to complete all the work in six hours.”

After putting in time as a crane oiler at Bonneville Dam, Rodriguez went to work for Kiewit Construction, where he spent 15 years. It took him six or seven years to complete his apprenticeship there, but he didn’t mind – the important thing was that he was staying busy. Three mentors took him under their wing and made sure he was consistently employed and accumulating new experience. They kept moving him from job to job and place to place, picking up new skills as he went along.

Those kinds of valuable connections with coworkers, Rodriguez learned, meant a lot when jobs lead to days and weeks away from home, staying in temporary living arrangements that afford you moments to really connect with your fellow workers.

“We get to talking, and, of course, we can’t help it,” Rodriguez reflects on these off-the-clock moments. “Pretty soon, we’re talking about this or that about our jobs. That’s been a great way to learn.” His work has led him to bunk down in a Lakeview, Oregon “man camp”, his own motor home for many years, in Astoria, and eventually, in Hawaii for a lifechanging three-year stint.

There’s something to be said for island living. “In Hawaii, I really learned a lot about working with people from many different cultures,” says Rodriguez. “It was a real adjustment getting used to the pace of work and life there.” He learned that he could “chill out a little” and still get his work accomplished, sans stress.

During his career, Rodriguez has moved from oiler to operator to crew chief to foreman – he’ll take the lead job when it’s requested — but he prefers “being in the seat.” “There is more to life than just working all the time,” says a man who prefers to spend his off hours with his girlfriend and her child over worrying about his career.

“Travel is a part of the life,” Rodriguez likes to say. His ability to adapt to new ways of doing things continues to serve him well in his professional life. “Each company has a different culture, too” he says. “For instance, one place really put a high value on keeping the equipment and vehicles clean and maintained. But at another outfit, they didn’t expect you to spend your time on much of that. They just assumed you’d be pretty rough on the equipment if you were really getting out there and working hard on your job.”

There is one consistent priority — safety. “You learn about safety every day,” he says. “Especially when people are operating big machines alongside of you, right next to your feet.” Rodriguez should know – he’s logged 25,000 workplace hours without an accident, advising new workers to be cautious because it can be easy to misjudge hazards when operating heavy equipment.

Advice to new workers from an old dirt hand? “Help others and along the way, never forget where you came from – that you were new once and everybody is always learning something.” Rodriguez adds his bottom line with a smile: “do the best job you can, but it’s okay to chill out a little too.”

Meet Renee Beaudoin, Apprentice Carpenter

One of the first projects that Portland’s Renee Beaudoin got involved in after graduating from Oregon Tradeswomen, Inc.’s (OTI) Trades and Apprenticeship Career Class (TACC) in 2011 was making phone calls to U.S. legislators. She was part of a team urging Senators and Congresspeople to support hiring women and people of color to work on the Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building modernization project.

She chuckles at the memory: “And then I ended up working here – kind of funny.”

It’s also a kind of linking of eras. One of the building’s namesakes, the late Oregon Congresswoman Edith Green, may be best known for Title IX, the part of the 1972 Higher Education Act that prohibited federally funded colleges and universities from discriminating against women. Title IX also opened the doors for girls to attend “shop” classes.

In high school, though, Renee was on a track toward healthcare. “I thought I wanted to do nursing or something like that,” she says. “I went through the whole health occupational program at Benson High School, but I didn’t ever look for any type of job in the healthcare industry.” Renee didn’t discover the trades until later, when she was serving a prison sentence and learned about OTI’s TACC program.

Now Renee is one of hundreds of tradespeople working on the modernization project, which will make the Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt building only the fifth LEED-certified federal building in the country. LEED stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design and the certification, developed by the U.S. Green Building Council, focuses on the design, construction and operation of high performance green buildings, homes and neighborhoods. This effort is classified as a federal “mega project” because the budget is over $50 million, its impact on the economy, the community, and its duration of more than two years. “It’s good to be part of the team. I look around and I see other women,” Renee says. “I feel really proud – I wish there were more (women on the project).”

In the program Renee is part of, a worker advances to the next level, or “term”, after 750 hours on the job, as a member of the carpenters union, Renee’s career is just getting started – and she loves it. “I’m excited that I’m going to be learning,” she says. “I’m just now at the very beginning of my career. Even my boss, who has been at it for 20 years now, says ‘I still learn something new every day.'”

Learning new things seems to come naturally to Renee. Once she found out about OTI, she was set to go. “I was really focused and knew exactly what I wanted to do,” she says. “But I didn’t know about the union or anything until I went through OTI’s TACC program.”

Renee is earning approximately the same weekly wage she was earning at her last job, working retail at a mall, but she is a lot happier. “Plus, I know I’m going to be moving up (in pay grade),” she says. Journey-level carpenters can make up to $32.00 an hour.

Renee added, “At the end of the day I can look back at all the work that I did for the day. And it’s like, cool, look at what I did!”